T4T LAB Spring 2016. Object Redux.

Invited Professor

Adam Fure

Team: Juan Arriaza, Stefani Johnson, Chris Bell, Sydney Farris, Madison Haynes

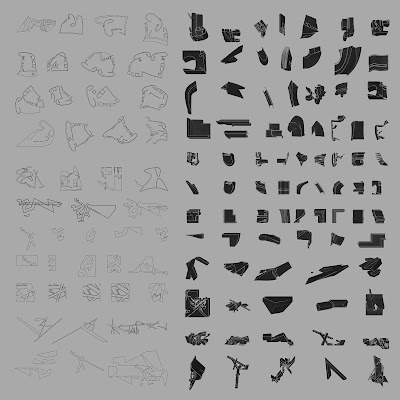

The experiment began as we became

interested in Ronchamp as a late modernist object where inside and outside are

separated by a fold between exterior and interior. Based on its main

organizational principles of continuous change around a central void,

transformation of wall to volume/ volume to wall and creation of entry through

the repetition of elements, we decided to reconfigure and distort elements and

extrude them to produce 3d manifestations of these. We began to denote these

new primitives as “chunks,” and proceeded to create an index from which compositions

were created. By sweeping, extruding, lofting, and booleaning shapes and forms

derived from the plan of Ronchamp individually, the group members then compiled

the sum of their work to assemble new objects. Through the process of combining and distorting chunks, elements

which once functioned as parts of a plan began to lose their definition and

begin to take on a new autonomy, driven by the inputs of each team member.

Trying to understand if the product

was a simple sum of different chunks, we decided to replicate the experiment

with a different building. The Jewish Museum was selected as it also follows an

irregular organization around a void as well as the

notion of the fragmented line as an organizing principle. The process of

reorganization of the plan and production of chunks was repeated to create a

new irreducible object.

In computing, from least to most

physical, there are four layers of information: application, transport,

internet, and link; where the application is the interface we actually engage

in and the link is the physical medium of transport. The deeper scripting

languages go and the further they move from our understanding, the more

boundless and raw the information becomes. The “critters” we engage with are

the most abstracted result of the plan of a real building; but while they’re

entirely hypothetical we are more able to interface with them than with the

original drawing, or data.

With Ronchamp and The Jewish Museum

as precedents, the plans are used as genetic framework from which “chunks” are

derived and categorized. The aforementioned process has been repeated so many

times that the final productions have logical depth, meaning a large amount of

data has been discarded to reach the final — a conventional design process with

an unconventional product. We began to ask: Does folding an object (in the

Deleuzian sense of The Fold) automatically create a new irreducible product or

is the folded object identical to the new object because it retains the same

formal qualities? The action of unfolding both opposes folding and continues

it.

Because each chunk was extracted and

operated on by different people, their ultimate combinations were the products

of entirely different evolutionary processes. Each “chunk” acts as a pixel in

that the assembly of all these similar building blocks reads as the unity of

infinitesimal parts. And each of the final conglomerations is the manifestation

of a variety of arrangements and productions. “The [referenced plan] becomes

distorted to such a degree as to render the [‘critter’] a denial of

repetition,” as it develops a particular character through its new autonomy.

Point-of-view is not limited to human perception. The irregularity and

lottery-like selection and combination of chunks creates a final model which

changes continuously around its axis, alternating from volume to wall, wall to

volume. The unity of the objects’ inherent multiplicity produces a gestalt

reading, as the self-organized chunks attain their own reality.

In this way, the project redefines

abstraction by unfolding rather than folding the original data.